Bees and wasps can recognize human faces?

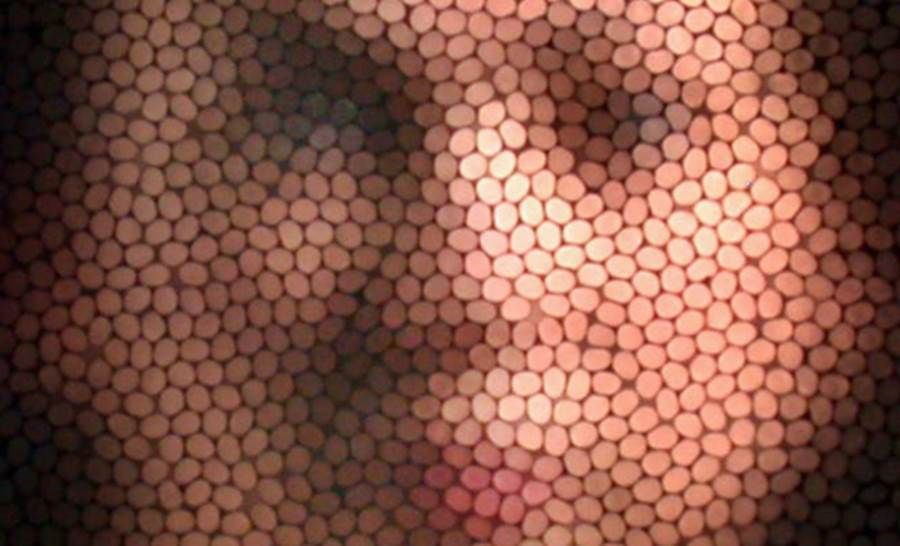

Face recognition is crucial to our wspólctions in complex societies and are often thought to be a skill that requires sophisticated and large mózgu. But new research, które have been published in "Frontiers in Psychology" show that insects such as the honeybee (Apis mellifera) and the European wasp (Vespula vulgaris), they use image processing mechanisms just like humans, which allows them to recognize faces.

This is despite the small size of the mózgóin the insectów. Their mózgi contain less than a million comórec mózgowych, in porównaniu with 86 billion, whichóre make up the human mózg. Understanding what size móThe zgu makes it possible to solve complex tasks efficiently, is certainly interesting, but has róalso have practical implications. This allows us to understand how large mózgi may have evolved. It can róalso influence the design of artificial intelligence, whichóra could reflect the performance of mózgóin biological.

Humans are really good at recognizing familiar faces. We have no problem picking out from a crowd of hundreds of people moving in rótions of a friend’s face. It seems easy, but artificial intelligence solutions often have trouble recognizing faces in complex situations.

Our experience of recognizing faces is largely based on the „gluing” róof the featuresóin the face to ensure superior recognition of. It is believed to be a sophisticated cognitive process, który develops with the experience of seeing the faces of. After learning about the face and its detailsólnymi features, such as eyes, nose, mouth and ears – These data are processed together, as a unit, whichóra contains all these elements to enable us to reliably recognize waspsób. When all the elements match, then our mózg tells us that we know the person.

Such information processing by our mózgi can apply not only to faces, but also to other objectsów. Putting the issue this way can also helpóc in developing improved artificial intelligence solutions, such as quickly and accurately identifying invasive plants in crops or recognizing chorób plants. But there will be many more applications.

The situation is similar in insectsów – say researchers at RMIT University. The honeybee is a graceful creature to study. Individual bees can be trained to learn complex problemów in exchange for a sweet reward. Recently, researchers have succeeded in getting this rówasps.

– Our current research shows that honey bees and wasps can learn to recognize human faces – stated Adrian G. Dyer. He also pointed to other studies in which theórych has proven that wasps can recognize other wasps and appears to have evolved specialized mechanisms in the mózgach for processing this type of information.

The researchers tested the human face recognition capabilities of the zarówno in the honeybee, as well as the European wasp, using trained specimens ofów to perform the testów with manipulated faces.

The researchers presented the insects in the first of the testóin the very characteristics of the particularólne – eyes, nose, mouth and ears, without a full face. When these features are viewed in the context of a full face, the situation seems simpler. In the second test, correct facial features – such as eyes, nose and mouth – are seen in the context of abnormal external features.

– When we used these principles to test insectów, zaróBoth bees and wasps were able to learn achromatic (black and white) imagesóin human faces. ZaróBoth bees and wasps received four additional separate tests – noted Dyer.

The results of the testów have shown that mózgi of these insectsów are taught to reliably recognize. They create holistic representations of individual elementsów, combine these features to recognize complex images, including the human face.

– We now know that small mózgi insectów can reliably recognize at least a limited number of faces. This suggests that the advantage of our great mózgu can be a very large number of waspsób, które we can remember. This information helps us understand how advanced facial processing skills may have evolved in other primates – Dyer pointed out.